It’s just a few days before your home loan is scheduled to close.

Your lender suddenly sends you their closing disclosure: a hefty document that highlights the terms of your loan and all the costs that come with it.

At a quick glance, it all seems to check off. The closing date is accurate. The mortgage terms are what you expect. The projected payments seem straightforward and manageable. But as you look through it more carefully, you start to run into terminology and numbers that confuse you. What seemed like a simple document is suddenly a scary obstacle to closing your home loan.

To help you overcome any confusion, we’ve broken down the sections in closing disclosures that elicit many questions: prepaids and initial escrow payments, paid by others, and paid already by or on behalf of borrower.

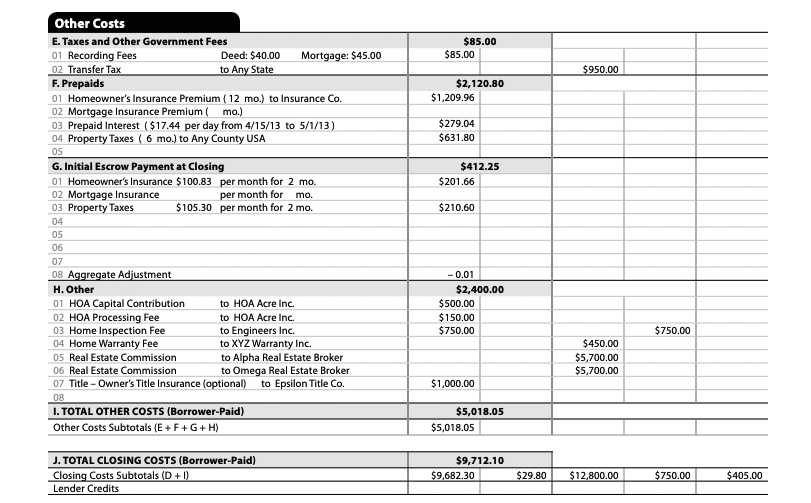

1. “Prepaids” + “Initial Escrow Payment at Closing”

On page 2 of your closing disclosure, you’ll see a few sections outlining additional costs you’ll need to pay before closing.

It should include your homeowner’s insurance, property taxes, and prepaid interest. All of the items listed are considered “prepaid” because you’re paying a certain amount for each ahead of schedule. Why does the lender do this? To improve the chances you stay current on them, and thereby protect their first lien position (e.g., if taxes are not current, the city or town could take lien priority from the lender).

Here’s a closer look at each of these items:

Prepaid interest

This is the interest on your mortgage that accrues from when you close through the end of that month. Your closing disclosure should clarify the fee by showing both the interest charge per day as well as the number of days included. The interest from subsequent monthly mortgage payments are paid in arrears. This means that whatever interest you’re charged in a given month was accrued from the previous month.

As an example, say your loan closes on February 13th. You would pay prepaid interest from Feb. 13th through the end of the month. Your first monthly mortgage payment would be on April 1st. This bill would account for the interest that accumulated in March.

Homeowner’s insurance

This covers you for damage to your home, its contents and loss of use arising from fires, certain natural disasters and crime. Your lender will almost certainly require some type of homeowner’s insurance as it protects you—and them—from unforeseen circumstances.

You’ll be expected to pay for the first 12 months of homeowner’s insurance at closing. The lender also requires at least 2 months of funds (or ⅙ of your annual policy) in escrow at all times that could go into covering your insurance.

Depending on when your loan closes, you may need another month of prepaid homeowner’s insurance to ensure you collect enough to pay for the 2nd year on the anniversary of your closing date—while maintaining the 2 months of funds needed in escrow.

We recommend consulting with your mortgage loan officer or processor several weeks before closing to review how much you’ll need to prepay for homeowner’s insurance—and whether that matches what’s in your closing disclosure.

Related article: Homeowner’s Insurance: What is it and what does it cover?

Property taxes

Your state’s property tax schedule in conjunction with your close date informs how much you owe in prepaid property taxes—versus how much the seller should pay. It’s also worth noting that similar to homeowner’s insurance, you’ll always need to have at least ⅙ of your annual property tax charges in escrow.

For example, say you’re buying a home in New Jersey. The state collects property taxes every 4 months—February, May, August, and November—and on the first day of those months.

Like our earlier example, let’s assume your close date is February 13th. The seller is responsible for the amount that accumulates from the beginning of the tax year up to the closing date—in other words, from January 1st through February 12th; while you the homebuyer will be responsible from February 13th through the end of April.

What does this mean? You’ll be responsible for putting your prorated tax amount (Feb 13th—end of April) in prepaids as well as ⅙ of the value of your annual property tax in your newly formed escrow account. You may also need an additional month (potentially 2) of taxes collected for the May payment.

To confirm the accuracy of the property tax amount outlined in your closing disclosure, we recommend researching your state’s position on property taxes and consulting with your MLO or processor.

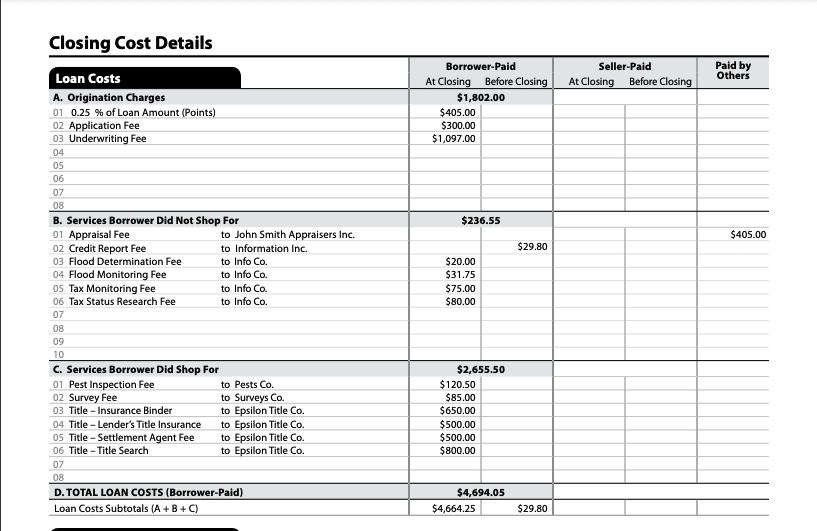

2. “Paid by Others”

To see what others pay, look at page 2 of the closing disclosure, in the column on the right.

Though you’ll likely be on the hook for most of your closing costs, the lender or broker will occasionally agree to cover some of these fees. For example, here at Morty, we waive your credit report and application fees. Take a quick look down the column to see if your lender or broker is still paying for the items they agreed to.

Also, if the lender is giving you credits—a payment that goes toward your closing costs in exchange for a higher rate—you might see certain items move from borrower-paid to paid by other, up to the sum of the credit value.

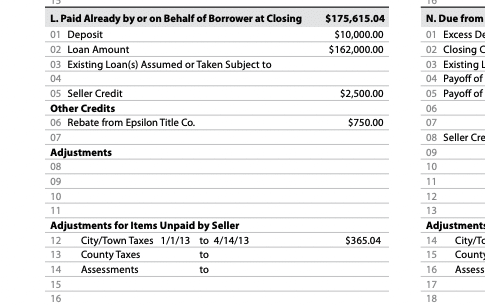

3. “Paid Already by or on Behalf of Borrower at Closing”

This section covers the items you can deduct from the total amount of cash needed to close. To find this section, look in the lower half of the 3rd page.

You may find any of the following:

- Deposit: Also known as an “earnest money deposit”, this is how much cash you put down as a security deposit when making an offer. It signals your commitment to buying the home as you may or may not get the money back if you fail to qualify for a loan or back out of the purchase. As long as the funds for the deposit can be verified by the institution that holds them, you can subtract the deposit from your cash to close.

- Loan amount: This is simply the total amount of your loan. Since you aren’t paying any of it back at the time of closing, it shouldn’t be part of your cash to close.

- Seller credits: These are funds the seller agrees to make toward your closing costs. You may or may not have them, as they’re typically negotiated during the bidding process. If you do, make sure they’re accounted for and subtracted from your cash to close.

- Lender credits: This is when the lender allocates a certain amount of money to help finance your closing costs—only now it’s in exchange for a higher interest rate. If you have this credit, confirm that it’s also subtracted from your cash to close.

- Prorated property taxes: This allocates the annual property tax bill to the buyer and seller based on the amount of time each side owns the property. The seller pays from the beginning of the current tax cycle until closing, where the buyer then becomes responsible. In other words, the borrower is only accountable when they legally own the home. You should see the amount your seller is responsible for in the “Adjustments and Other Credits” section—and it should be subtracted from your cash to close.

As we mentioned before, since every state collects property taxes at different frequencies and times of the year, we recommend researching your state’s policies and consulting with your MLO or processor before confirming the tax-related numbers in your closing disclosure.

Now that you understand these more complicated fields in the closing disclosure, you should feel comfortable going back to yours and reviewing it with confidence!

A closing date you can count on.

With Morty’s Closing Date Promise, we’ll make your closing date—or you get $2,000.